Tour de France History

The Tour de France: then and now

Le Tour de France has been pushing man and machine to their limits since 1903. But much has changed since the early days of the Tour: from a mostly national attraction, it has become the world’s largest annual multi-day sporting event, drawing billions of fans from across the globe. On the road, too, things are a lot different: safer, more professional and a little less wild. Join us on a ride down memory lane to find out more.

What´s changed? The history of the Tour de France

The first Tour de France was held in 1903 – with the aim of selling more newspapers… It was set up and sponsored by French sports paper L’Auto, which hoped a tough new endurance race around the country would capture the public’s attention and boost its declining sales figures. It was right. The race was a hit, and tens of thousands gathered in Paris to witness its final stage – much like they do today. But many other things have changed dramatically since the first Tour in 1903.

Tour history

1903: A Race to Boost Sales

The Tour was born as a marketing ploy by a French newspaper, L’Auto, to boost circulation. The first edition, a brutal six-stage trek across France, saw Frenchman Maurice Garin crowned the champion.

1919: The Yellow Jersey Emerges:

The iconic yellow jersey, signifying the overall race leader, debuted. Eugene Christophe became the first rider to wear it with pride.

1920s: International Expansion

The Tour’s fame grew, attracting riders beyond France. Italian legend Ottavio Bottecchia secured back-to-back victories in 1924 and 1925.

1930s: Technological Advancements

The 1930s saw the introduction of derailleurs, allowing riders to shift gears more efficiently. French riders dominated this era, winning six Tours in a row.

Post-War Growth and Prestige

The Tour persevered through World War II and emerged even stronger. New team structures and media coverage like radio broadcasts further solidified the Tour’s status as the most prestigious cycling race in the world.

The Modern Tour

The modern Tour de France continues to push the boundaries of cycling with cutting-edge technology, international rivalries, and grueling routes that test the limits of human endurance.

The 2024 Tour de France Stats

3,492

22

10-12

From reckless riders to dedicated sports pros

The Evolution

Tour de France cyclists have always been incredibly fit and dedicated to their craft. But in the early days of the race, competitors had somewhat more relaxed views on training and diet.

From Past to Present

Booze in the Tour

Alcohol was a staple for many riders, even during a race. 1903 Tour de France winner Maurice Garin was a fan of wine and cigarettes and liked to break at several bars en route to ‘refuel’. In 1935, almost the entire peloton stopped to have a drink with locals! Of course, strenuous exercise requires cyclists to take on plenty of carbohydrates and calories, but back then there was little concern for nutritional value. The 1904 Tour de France winner, Henri Cornet, favored a diet that included plenty of hot chocolate, tea, champagne and rice pudding.

Today’s Pros

By comparison, today’s pros dedicate almost every single day to staying fit and healthy. The cycling season runs from February to October and teams meticulously plan everything for their riders to ensure they peak at the right time.

Diets Are Carefully Managed

While training schedules include everything from gym sessions and yoga to massages and stretching, as well as plenty of hours in the saddle. During the Tour, depending on stage difficulty, riders can eat up to 7,000 calories a day – three times what average humans burn in a day.

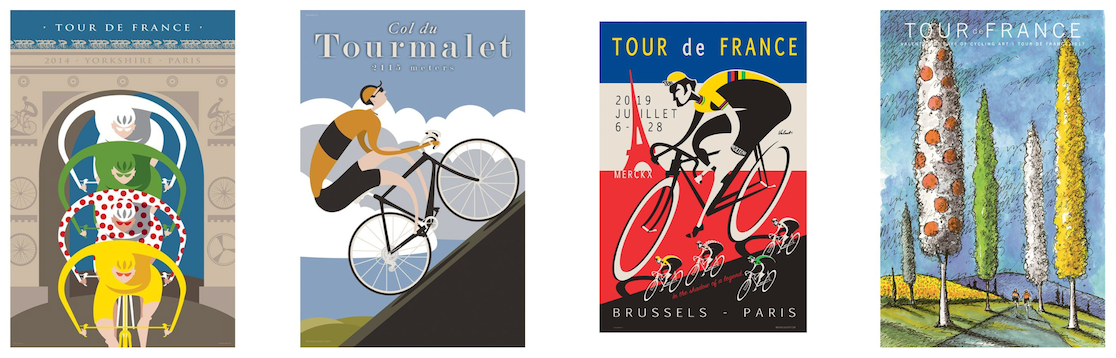

Understanding the 4 Jerseys

Yellow Jersey

For most, the race’s fabled yellow jersey, or maillot jaune, stands above all else, as it designates the rider who leads the General Classification.

Polka Dot Jersey

The polka dot jersey goes to the leader of the Mountains Classification, otherwise known as King of the Mountains.

White Jersey

The white jersey, or maillot blanc, goes to the General Classification leader who is 25 years old or younger (on January 1 in the given race year).

Green Jersey

While known as the “sprinter’s jersey,” the green jersey goes to the leader of the Points Classification.

How are Points Awarded?

The point distribution for the mountains in the 2019 event was:

| Type | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th | 6th | 7th | 8th |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hors Category | 20 | 15 | 12 | 10 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 2 |

| First Category | 10 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Second Category | 5 | 3 | 2 | 1 | ||||

| Third Category | 2 | 1 | ||||||

| Fourth Category | 1 |

A history of road racing

First Tour de France Winner

French cyclist Maurice Garin, the first Tour de France winner, rode on a bike considerably different to those used today (and without wearing a helmet). Thanks to a steel frame and wooden rims, it weighed in at a bulky 18 kilograms, significantly more than twice as much as today’s machines. And the bikes weren’t just heavy, they were also single speed, making climbing particularly strenuous.

Racing Alone without Support

To make things harder still, cyclists raced alone – without team cars or spare bikes. They would wrap themselves in spare tires and inner tubes like ammunition belts in preparation for the inevitable punctures.

Modern Cutting Edge Equipment

In the past few years, riders tackle each stage of the Tour de France on cutting-edge carbon fiber bikes that weigh around seven kilograms. They’ll even have a choice of styles for different types of stage: flat, mountain or time trial. Helmets are now compulsory.

Team Support

Supporting each team is a squad of backroom staff comprising a general manager, multiple directors, mechanics, a chef, doctor and masseurs. While they’re on the road, riders are in constant contact with their team via radio and have access to spare bikes, clothing, food and drink in support cars.

Experience the Modern Tour First Hand

CRAZY Tour de France on-bike footage | Best on-bike highlights

This is amazing! It shows the race dynamics much better than any external camera.

Seriously beautiful… The ovation for each rider in each climb is absolutely the most inspiring things ever to see.

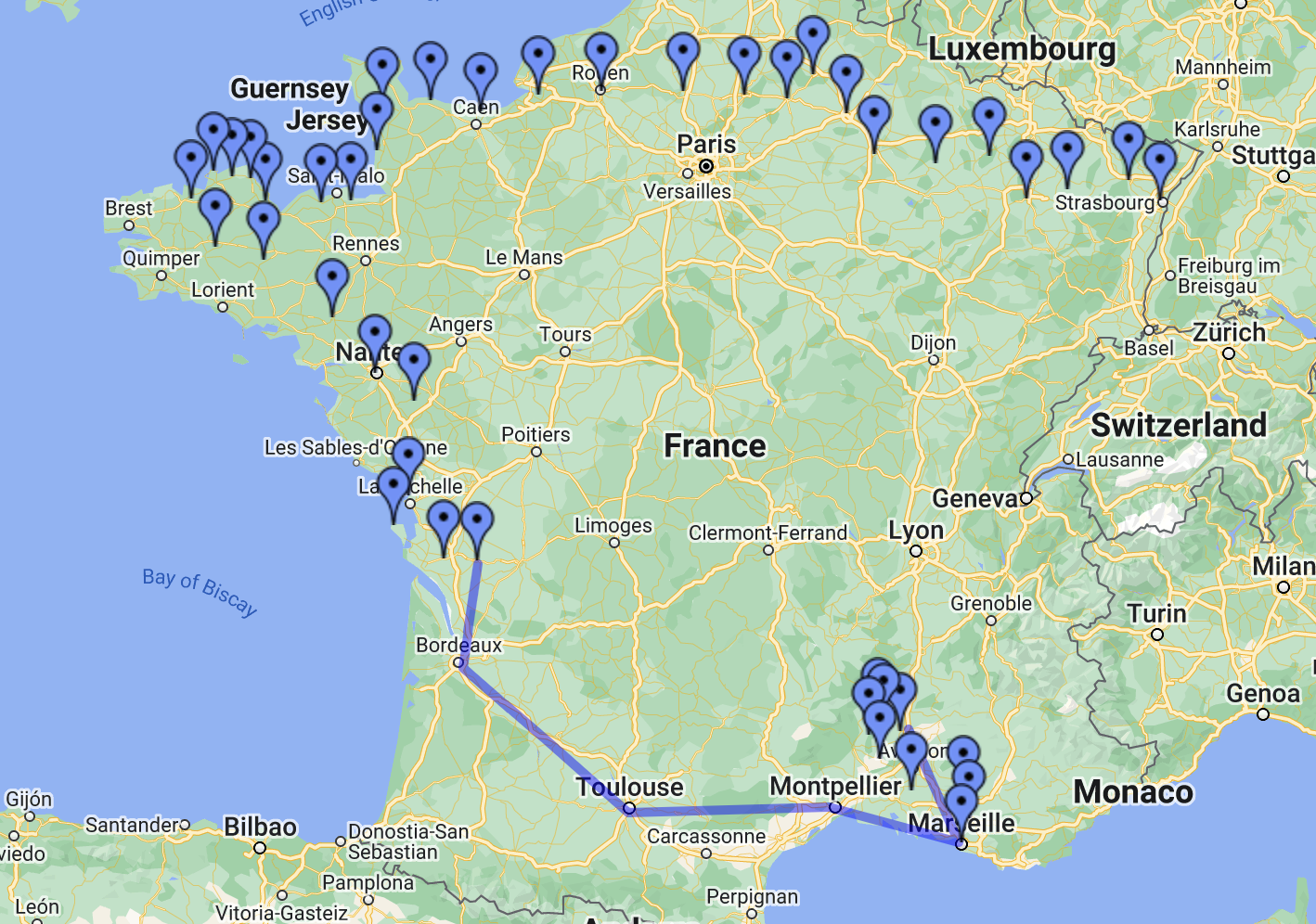

Tour de France 2012 Route

Explore the 2012 tour map.

The rise and fall of Lance Armstrong

During Indurain’s reign another American was emerging; Lance Armstrong won a stage in the 1993 and 1995 Tours. Diagnosed with testicular cancer in 1996, Armstrong was given a slim chance of living, since it had also spread to various parts of his body and brain. Following an operation and painful chemotherapy, he fought back with a vengeance and won the 1999 Tour de France. He never looked back, joined the élite club of Anquetil, Merckx, Hinault and Indurain by winning five Tours… and then went two better. However, he had these winnings stripped after a lengthy doping investigation.

Culture

The Tour is an important cultural event for fans in Europe. Millions[153] line the route, some having camped for a week to get the best view.

The Tour de France appealed from the start not just for the distance and its demands but because it played to a wish for national unity, a call to what Maurice Barrès called the France “of earth and deaths” or what Georges Vigarello called “the image of a France united by its earth.”

School book by Augustine Fouillée under the ‘nom de plume’ G. Bruno

The image had been started by the 1877 travel/school book Le Tour de la France par deux enfants. It told of two boys, André and Julien, who “in a thick September fog left the town of Phalsbourg in Lorraine to see France at a time when few people had gone far beyond their nearest town.”

The book sold six million copies by the time of the first Tour de France, the biggest selling book of 19th-century France (other than the Bible).

It stimulated a national interest in France, making it “visible and alive”, as its preface said. There had already been a car race called the Tour de France but it was the publicity behind the cycling race, and Desgrange’s drive to educate and improve the population, that inspired the French to know more of their country.

The academic historians Jean-Luc Boeuf and Yves Léonard say most people in France had little idea of the shape of their country until L’Auto began publishing maps of the race.

Arts

The Tour has inspired several popular songs in France, notably P’tit gars du Tour (1932), Les Tours de France (1936) and Faire le Tour de France (1950). German electronic group Kraftwerk composed “Tour de France” in 1983 – described as a minimalistic “melding of man and machine” – and produced an album, Tour de France Soundtracks in 2003, the centenary of the Tour.

The Tour and its first Italian winner, Ottavio Bottecchia, are mentioned at the end of Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises.

From 2011 to 2015, Lead Graffiti, an American letterpress studio, experimented with handset wood and metal type to print same-day posters documenting events of each stage of the Tour de France. The designers called the project “endurance letterpress.” A 2013 article on the poster series appeared in Sports Illustrated magazine’s “Sports in Media” issue. In 2014 the British Library celebrated the Tour’s fourth Grand Départ from the U.K. with an exhibition of Tour de Lead Graffiti posters.

In films, the Tour was background for Five Red Tulips (1949) by Jean Stelli, in which five riders are murdered. A burlesque in 1967, Les Cracks by Alex Joffé, with Bourvil et Monique Tarbès, also featured it. Footage of the 1970 Tour de France is shown in Jorgen Leth’s experimental short Eddy Merckx in the Vicinity of a Cup of Coffee. Patrick Le Gall made Chacun son Tour (1996). The comedy, Le Vélo de Ghislain Lambert (2001), featured the Tour of 1974.

In 2005, three films chronicled a team. The German Höllentour, translated as Hell on Wheels, recorded 2003 from the perspective of Team Telekom. The film was directed by Pepe Danquart, who won an Academy Award for live-action short film in 1993 for Black Rider (Schwarzfahrer). The Danish film Overcoming by Tómas Gislason recorded the 2004 Tour from the perspective of Team CSC.

Wired to Win chronicles Française des Jeux riders Baden Cooke and Jimmy Caspar in 2003. By following their quest for the points classification, won by Cooke, the film looks at the working of the brain. The film, made for IMAX theaters, appeared in December 2005. It was directed by Bayley Silleck, who was nominated for an Academy Award for documentary short subject in 1996 for Cosmic Voyage.

A fan, Scott Coady, followed the 2000 Tour with a handheld video camera to make The Tour Baby! which raised $160,000 to benefit the Lance Armstrong Foundation, and made a 2005 sequel, Tour Baby Deux!

Vive Le Tour by Louis Malle is an 18-minute short of 1962. The 1965 Tour was filmed by Claude Lelouch in Pour un Maillot Jaune. This 30-minute documentary has no narration and relies on sights and sounds of the Tour.

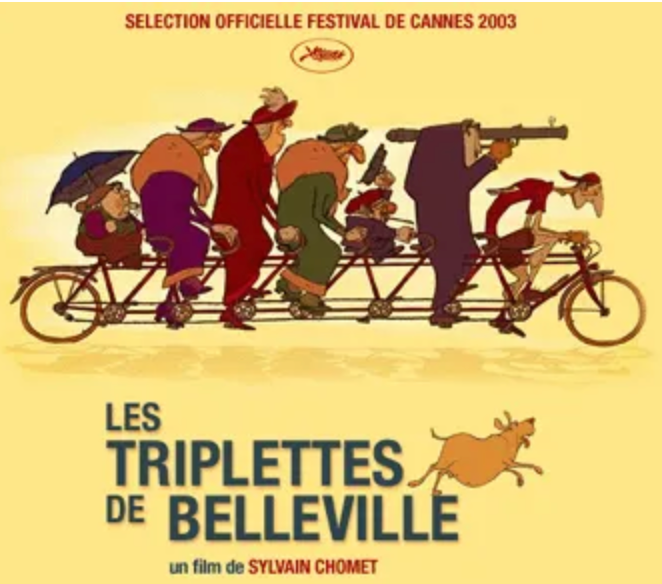

Les Triplettes de Belleville (The Triplets of Belleville)

Fictional, Animated, Bizarre

In fiction, the 2003 animated feature Les Triplettes de Belleville (The Triplets of Belleville) ties into the Tour de France.

Netflix, partnered with the organizer Amaury Sport Organisation, has produced a documentary series about the eight major teams across the 2022 Tour de France named Tour de France: Unchained. It was released in June 2023.

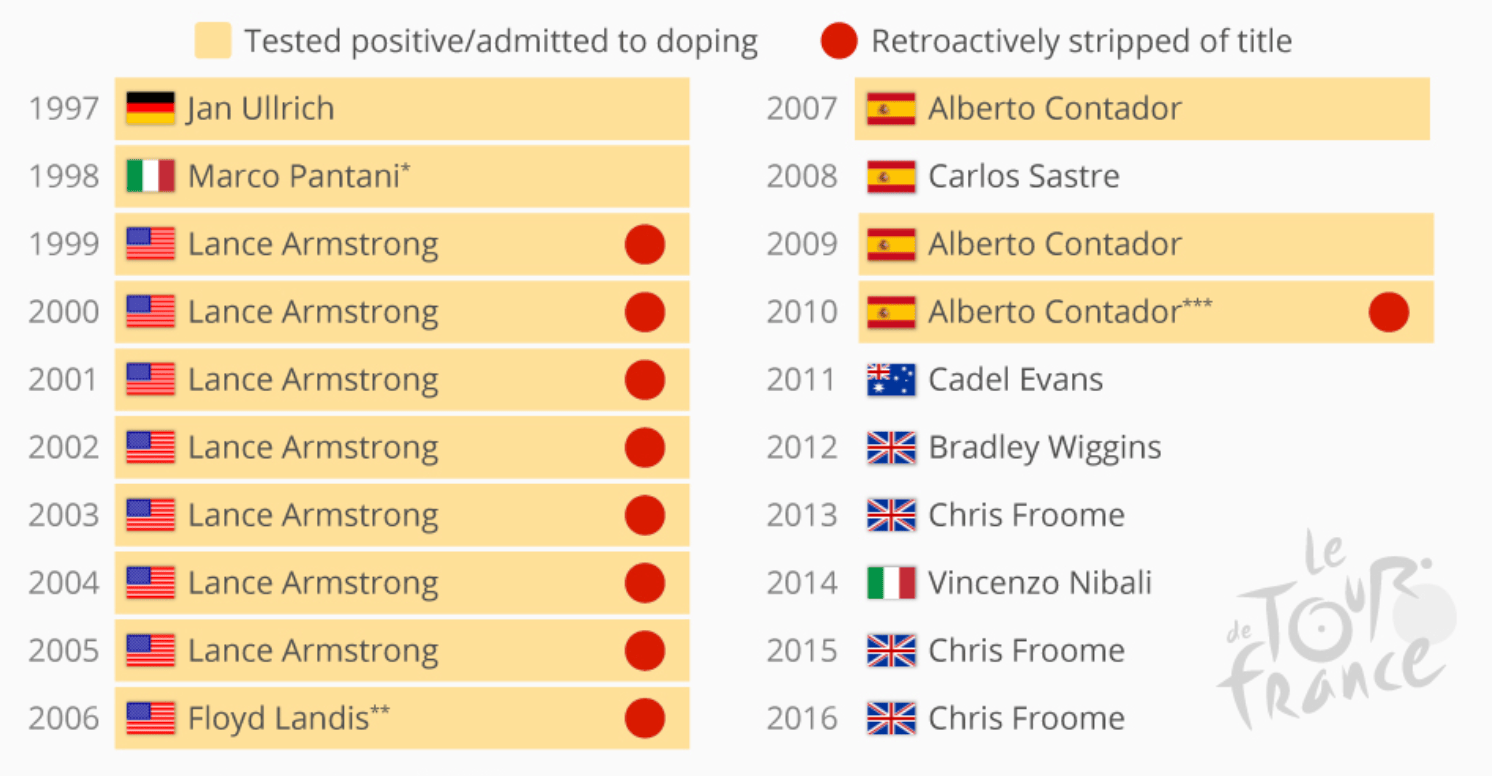

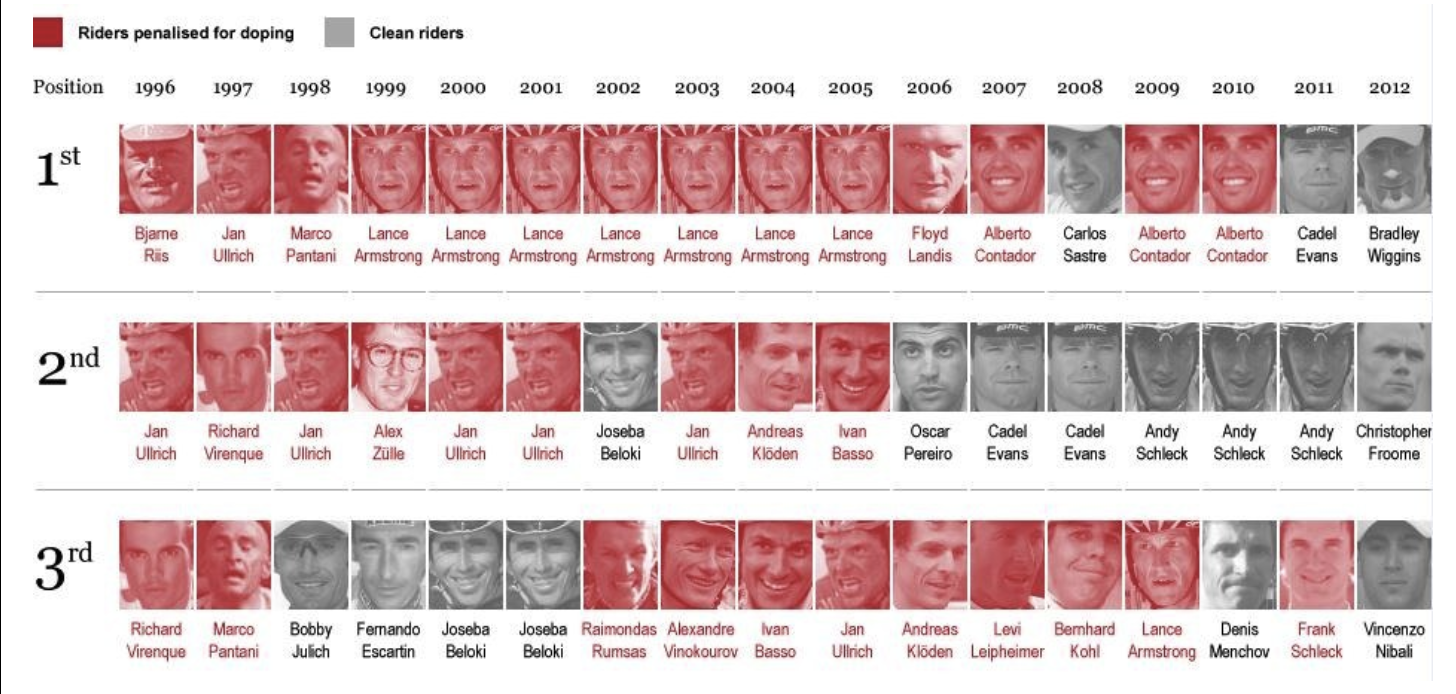

Doping & The Tour

Allegations of doping have plagued the Tour almost since 1903. Early riders consumed alcohol and used ether to dull the pain. Over the years they began to increase performance and the Union Cycliste Internationale and governments enacted policies to combat the practice.

In 1924, Henri Pélissier and his brother Charles told the journalist Albert Londres they used strychnine, cocaine, chloroform, aspirin, “horse ointment” and other drugs. The story was published in Le Petit Parisien under the title Les Forçats de la Route (‘The Convicts of the Road’)

On 13 July 1967, British cyclist Tom Simpson died climbing Mont Ventoux after taking amphetamine.

In 1998, the “Tour of Shame”, Willy Voet, soigneur for the Festina team, was arrested with erythropoietin (EPO), growth hormones, testosterone and amphetamine. Police raided team hotels and found products in the possession of the cycling team TVM. Riders went on strike. After mediation by director Jean-Marie Leblanc, police limited their tactics and riders continued. Some riders had dropped out and only 96 finished the race. It became clear in a trial that management and health officials of the Festina team had organised the doping.

Further measures were introduced by race organisers and the UCI, including more frequent testing and tests for blood doping (transfusions and EPO use). This would lead the UCI to becoming a particularly interested party in an International Olympic Committee initiative, the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA), created in 1999. In 2002, the wife of Raimondas Rumšas, third in the 2002 Tour de France, was arrested after EPO and anabolic steroids were found in her car. Rumšas, who had not failed a test, was not penalised. In 2004, Philippe Gaumont said doping was endemic to his Cofidis team. Fellow Cofidis rider David Millar confessed to EPO after his home was raided. In the same year, Jesús Manzano, a rider with the Kelme team, alleged he had been forced by his team to use banned substances.

From 1999 to 2005, seven successive tours were declared as having been won by Lance Armstrong. In August 2005, one month after Armstrong’s seventh apparent victory, L’Équipe published documents it said showed Armstrong had used EPO in the 1999 race. At the same Tour, Armstrong’s urine showed traces of a glucocorticosteroid hormone, although below the positive threshold. He said he had used skin cream containing triamcinolone to treat saddle sores. Armstrong said he had received permission from the UCI to use this cream. Further allegations ultimately culminated in the United States Anti Doping Agency (USADA) disqualifying him from all his victories since 1 August 1998, including his seven consecutive Tour de France victories, and a lifetime ban from competing in professional sports. The ASO declined to name any other rider as winner in Armstrong’s stead in those years.

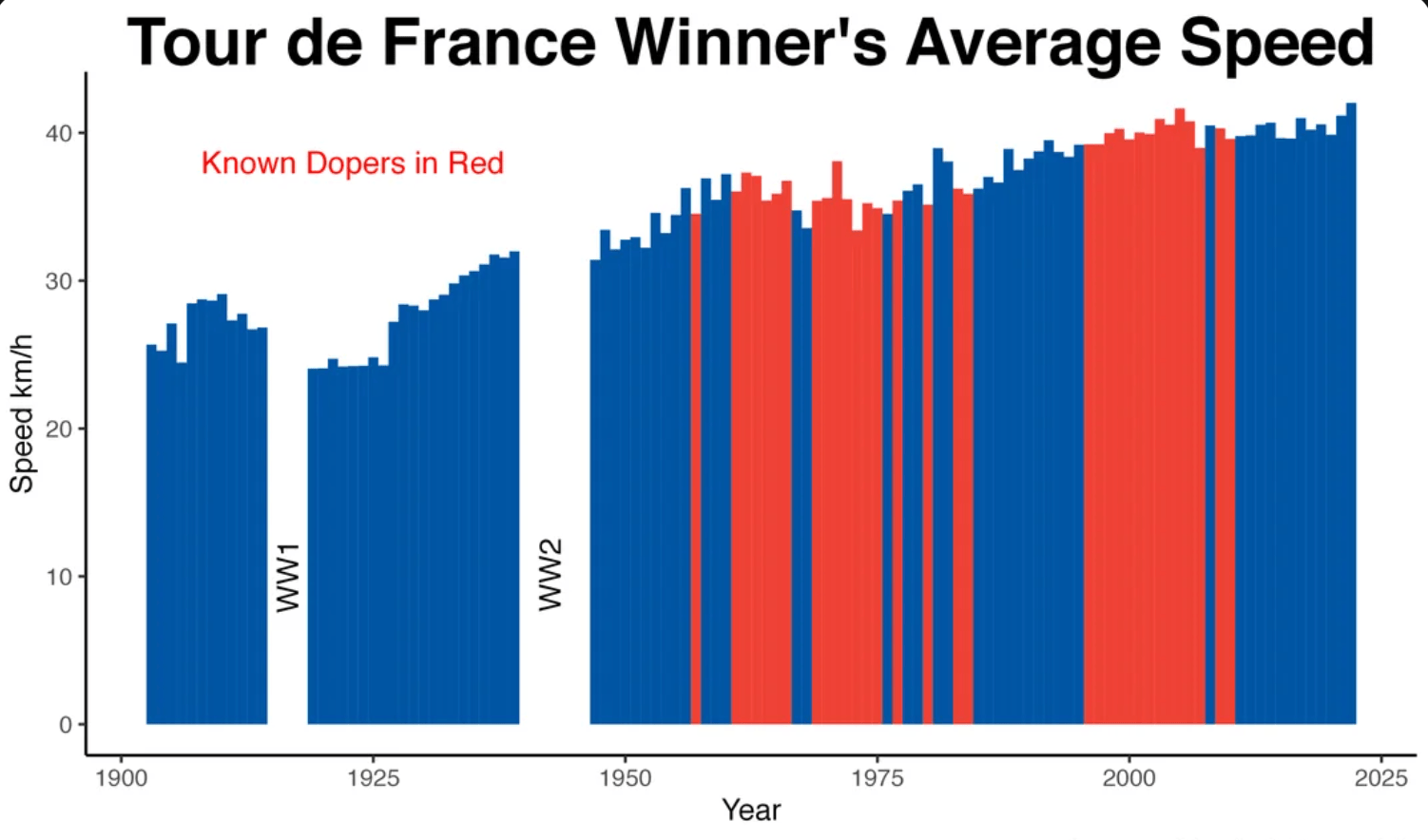

Tour de France Winners Average Speed

The 2006 Tour had been plagued by the Operación Puerto doping case before it began. Favourites such as Jan Ullrich and Ivan Basso were banned by their teams a day before the start. Seventeen riders were implicated. American rider Floyd Landis, who finished the Tour as holder of the overall lead, had tested positive for testosterone after he won stage 17, but this was not confirmed until some two weeks after the race finished. On 30 June 2008 Landis lost his appeal to the Court of Arbitration for Sport, and Óscar Pereiro was named as winner.

On 24 May 2007, Erik Zabel admitted using EPO during the first week of the 1996 Tour, when he won the points classification. Following his plea that other cyclists admit to drugs, former winner Bjarne Riis admitted in Copenhagen on 25 May 2007 that he used EPO regularly from 1993 to 1998, including when he won the 1996 Tour. His admission meant the top three in 1996 were all linked to doping, two admitting cheating. On 24 July 2007 Alexander Vinokourov tested positive for a blood transfusion (blood doping) after winning a time trial, prompting his Astana team to pull out and police to raid the team’s hotel. The next day Cristian Moreni tested positive for testosterone. His Cofidis team pulled out.

The same day, leader Michael Rasmussen was removed for “violating internal team rules” by missing random tests on 9 May and 28 June. Rasmussen claimed to have been in Mexico. The Italian journalist Davide Cassani told Danish television he had seen Rasmussen in Italy. The alleged lying prompted Rasmussen’s firing by Rabobank.

Manuel Beltrán tested positive

EPO in the Tour

On 11 July 2008, Manuel Beltrán tested positive for EPO after the first stage. On 17 July 2008, Riccardo Riccò tested positive for continuous erythropoiesis receptor activator, a variant of EPO, after the fourth stage. In October 2008, it was revealed that Riccò’s teammate and Stage 10 winner Leonardo Piepoli, as well as Stefan Schumacher – who won both time trials – and Bernhard Kohl – third on general classification and King of the Mountains – had tested positive.

After winning the 2010 Tour de France, it was announced that Alberto Contador had tested positive for low levels of clenbuterol on 21 July rest day. On 26 January 2011, the Spanish Cycling Federation proposed a 1-year ban but reversed its ruling on 15 February and cleared Contador to race. Despite a pending appeal by the UCI, Contador finished fifth overall in the 2011 Tour de France, but in February 2012, Contador was suspended and stripped of his 2010 victory.

During the 2012 Tour, the 3rd placed rider from 2011, Fränk Schleck, tested positive for the banned diuretic Xipamide and was immediately disqualified from the Tour.

In October 2012, the United States Anti-Doping Agency released a report on doping by the U.S. Postal Service cycling team, implicating, amongst others, Armstrong. The report contained affidavits from riders including Frankie Andreu, Tyler Hamilton, George Hincapie, Floyd Landis, Levi Leipheimer, and others describing widespread use of Erythropoietin (EPO), blood transfusion, testosterone, and other banned practices in several Tours.In October 2012 the UCI acted upon this report, formally stripping Armstrong of all titles since 1 August 1998, including all seven Tour victories, and announced that his Tour wins would not be reallocated to other riders.

While no Tour winner has been convicted, or even seriously accused of doping in order to win the Tour in the past decade, due to the previous era, questions frequently arise when a strong performance exceeds expectations. While four-time champion Froome has been involved in a doping case, it is out of an abundance of caution that modern riders are kept under a microscope with bike inspections to check for “mechanical doping” as well as Biological Passports as officials try not to have a repeat of EPO with ‘H7379 Haemoglobin Human’. Despite initially beginning as an operation to investigate the winter sport of Nordic Skiing, Operation Aderlass is of particular interest to this sport because it involved people formerly and presently involved in cycling. Including the since vacated 2008 podium finisher Bernhard Kohl, who made accusations that a team doctor instructed riders how to dope, which prompted further investigation into this matter by authorities.

Records and Statistics

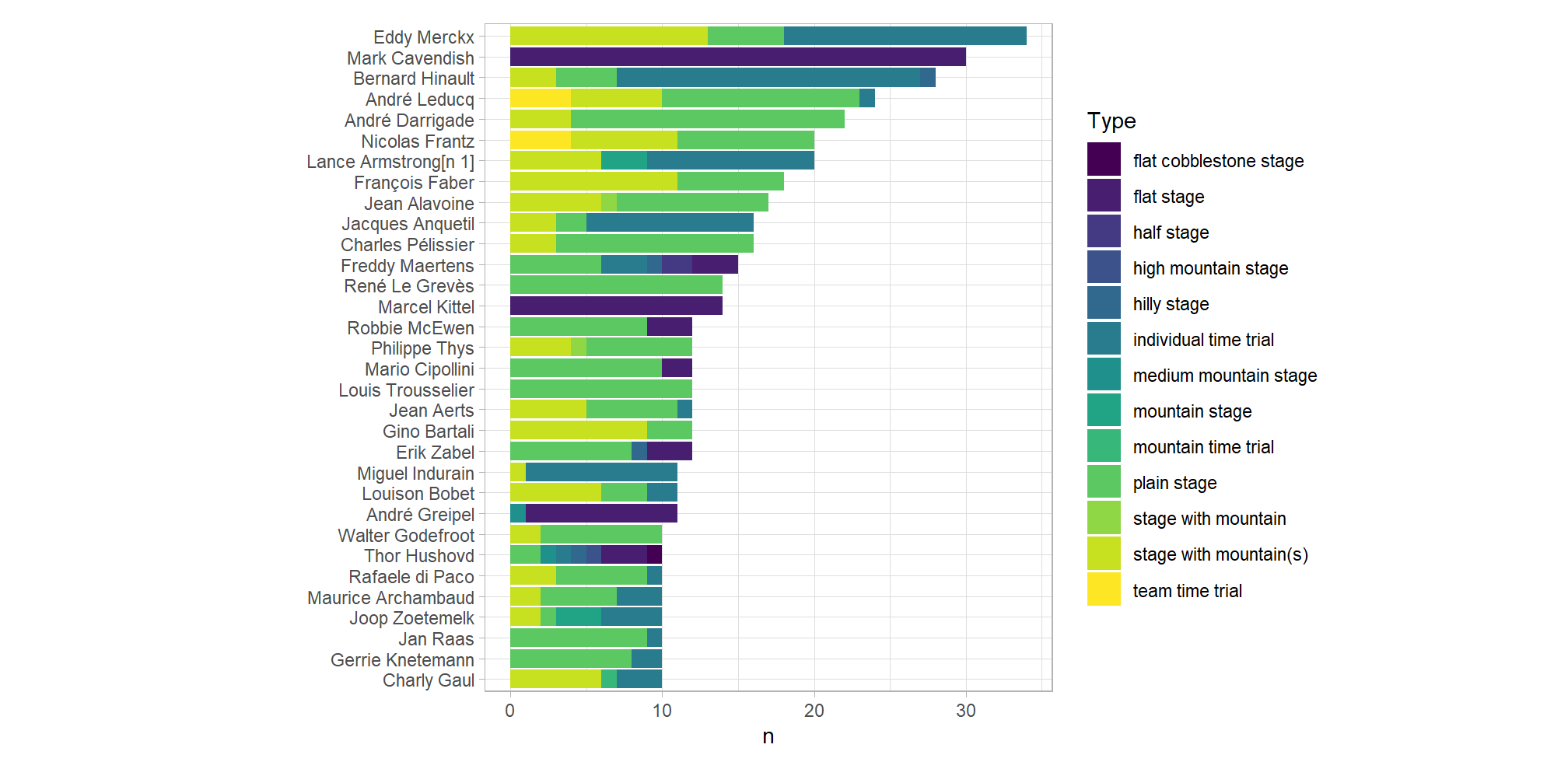

One rider has been King of the Mountains, won the combination classification, combativity award, the points competition, and the Tour in the same year—Eddy Merckx in 1969, which was also the first year he participated. The following year he came close to repeating the feat, but was five points behind the winner in the points classification. The only other rider to come close to this achievement is Bernard Hinault in 1979, who won the overall and points competitions and placed second in the mountains classification.

Twice the Tour was won by a racer who never wore the yellow jersey until the race was over. In 1947, Jean Robic overturned a three-minute deficit on the 257 kilometres (160 mi) final stage into Paris. In 1968, Jan Janssen of the Netherlands secured his win in the individual time trial on the last day.

The Tour has been won three times by racers who led the general classification on the first stage and holding the lead all the way to Paris. Maurice Garin did it during the Tour’s first edition, 1903; he repeated the feat the next year, but the results were nullified by the officials as a response to widespread cheating. Ottavio Bottecchia completed a GC start-to-finish sweep in 1924. And in 1928, Nicolas Frantz held the GC for the entire race, and at the end, the podium consisted solely of members of his racing team. While no one has equalled this feat since 1928, four times a racer has taken over the GC lead on the second stage and carried that lead all the way to Paris. Jacques Anquetil predicted he would wear the yellow jersey as leader of the general classification from start to finish in 1961, which he did. That year, the first day had two stages, the first part from Rouen to Versailles and the second part from Versailles to Versailles. André Darrigade wore the yellow jersey after winning the opening stage but Anquetil was in yellow at the end of the day after the time trial.

The most appearances record is held by Sylvain Chavanel, who rode his 18th and final Tour in 2018. Prior to Chavanel’s final Tour, he shared the record with George Hincapie with 17. In light of Hincapie’s suspension for use of performance-enhancing drugs, before which he held the mark for most consecutive finishes with sixteen, having completed all but his very first, Joop Zoetemelk and Chavanel share the record for the most finishes at 16, with Zoetemelk having completed all 16 of the Tours that he started. Of these 16 Tours Zoetemelk came in the top five 11 times, a record, finished 2nd six times, a record, and won the 1980 Tour de France.

Between 1920 and 1985, Jules Deloffre (1885–1963) was the record holder for the number of participations in the Tour de France, and even sole holder of this record until 1966, when André Darrigade rode in his 14th Tour.

In the early years of the Tour, cyclists rode individually, and were sometimes forbidden to ride together. This led to large gaps between the winner and the number two. Since the cyclists now tend to stay together in a peloton, the margins of the winner have become smaller, as the difference usually originates from time trials, breakaways or on mountain top finishes, or from being left behind the peloton. The smallest margins between the winner and the second placed cyclists at the end of the Tour is 8 seconds between winner Greg LeMond and Laurent Fignon in 1989. The largest margin, by comparison, remains that of the first Tour in 1903: 2h 49m 45s between Maurice Garin and Lucien Pothier.

The most podium places by a single rider is eight by Raymond Poulidor, followed by Bernard Hinault and Joop Zoetemelk with seven. Poulidor never finished in 1st place and neither Hinault nor Zoetemelk ever finished in 3rd place.

Lance Armstrong finished on the podium eight times, and Jan Ullrich seven times, however they both had results voided and now officially have zero and six podiums respectively.

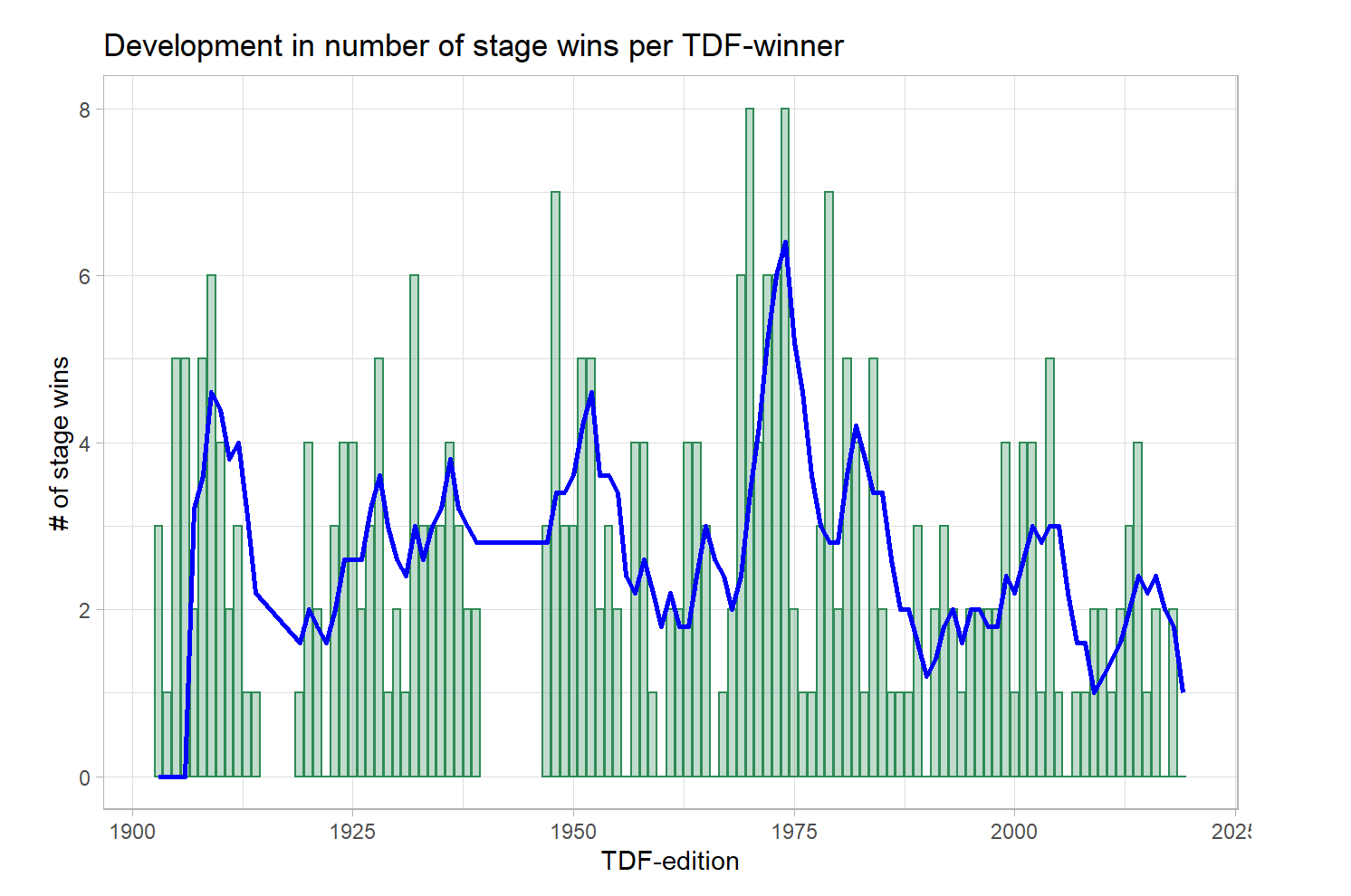

Three riders have won 8 stages in a single year: Charles Pélissier (1930), Eddy Merckx (1970, 1974), and Freddy Maertens (1976). Mark Cavendish has the most mass finish stage wins with 34 as of stage 13 in 2021, ahead of André Darrigade and André Leducq with 22, François Faber with 19, and Eddy Merckx with 18. The youngest Tour de France stage winner is Fabio Battesini, who was 19 when he won one stage in the 1931 Tour de France.

The fastest massed-start stage was in 1999 from Laval to Blois (194.5 kilometres (120.9 mi)), won by Mario Cipollini at 50.4 kilometres per hour (31.3 mph). The fastest time-trial is Rohan Dennis’s stage 1 of the 2015 Tour de France in Utrecht, won at an average of 55.446 kilometres per hour (34.453 mph). The fastest stage win was by the 2013 Orica GreenEDGE team in a team time-trial. It completed the 25 kilometres (16 mi) in Nice (stage 5) at 57.8 kilometres per hour (35.9 mph).

The longest successful post-war breakaway by a single rider was by Albert Bourlon in the 1947 Tour de France. In the Carcassonne–Luchon stage, he stayed away for 253 kilometres (157 mi). It was one of seven breakaways longer than 200 kilometres (120 mi), the last being Thierry Marie’s 234 kilometres (145 mi) escape in 1991. Bourlon finished 16 m 30s ahead. This is one of the biggest time gaps but not the greatest. That record belongs to José-Luis Viejo, who beat the peloton by just over 23:00 and the second place rider by 22 m 50s in the Montgenèvre-Manosque stage in 1976.He was the fourth and most recent rider to win a stage by more than 20 minutes.

The record for total number of days wearing the yellow jersey is 96, held by Eddy Merckx. Bernard Hinault, Miguel Induráin, Chris Froome and Jacques Anquetil are the only other riders who have worn it 50 days or more.

Tour de France Podiums Won by Nation 1903 – 2016

| Nation | Tour wins | 2nd place | 3rd place | Total podiums | Percent of wins | Percent of podiums |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0.0% | 0.6% |

| Australia | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 1.0% | 1.0% |

| Belgium | 18 | 15 | 16 | 49 | 17.5% | 15.9% |

| Colombia | 0 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 0.0% | 1.3% |

| Denmark | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1.0% | 0.6% |

| France | 36 | 31 | 33 | 100 | 35.0% | 32.4% |

| Germany | 1 | 8 | 1 | 10 | 1.0% | 3.2% |

| Ireland | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1.0% | 0.6% |

| Italy | 10 | 16 | 15 | 41 | 9.7% | 13.3% |

| Kazakhstan | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.0% | 0.3% |

| Latvia | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.0% | 0.3% |

| Lithuania | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.0% | 0.3% |

| Luxembourg | 4 | 7 | 3 | 14 | 3.9% | 4.5% |

| Netherlands | 2 | 10 | 3 | 15 | 1.9% | 4.9% |

| Poland | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.0% | 0.3% |

| Portugal | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0.0% | 0.6% |

| Russia | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.0% | 0.3% |

| Spain | 13 | 5 | 12 | 30 | 12.6% | 9.7% |

| Sweden | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.0% | 0.3% |

| Switzerland | 2 | 4 | 3 | 9 | 1.9% | 2.9% |

| United Kingdom | 4 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 3.9% | 1.6% |

| United States | 10 | 1 | 4 | 15 | 9.7% | 4.9% |

| Total | 103 | 103 | 103 | 309 | 100.0% | 100.0% |

Broadcasting

The Tour was first followed only by journalists from L’Auto, the organisers. The race was founded to increase sales of a floundering newspaper and its editor, Desgrange, saw no reason to allow rival publications to profit. The first time papers other than L’Auto were allowed was 1921, when 15 press cars were allowed for regional and foreign reporters.

The Tour was shown first on cinema newsreels a day or more after the event. The first live radio broadcast was in 1929, when Jean Antoine and Alex Virot of the newspaper L’Intransigeant broadcast for Radio Cité. They used telephone lines. In 1932 they broadcast the sound of riders crossing the col d’Aubisque in the Pyrenees on 12 July, using a recording machine and transmitting the sound later.

The first television pictures were shown a day after a stage. The national TV channel used two 16mm cameras, a Jeep, and a motorbike. Film was flown or taken by train to Paris, where it was edited and then shown the following day.

The first live broadcast, and the second of any sport in France, was the finish at the Parc des Princes in Paris on 25 July 1948. Rik Van Steenbergen of Belgium led in the bunch after a stage of 340 kilometres (210 mi) from Nancy. The first live coverage from the side of the road was from the Aubisque on 8 July 1958. Proposals to cover the whole race were abandoned in 1962 after objections from regional newspapers whose editors feared the competition. The dispute was settled, but not in time for the race, and the first complete coverage was the following year in 1963. In 1958 the first mountain climbs were broadcast live on television for the first time, and in 1959 helicopters were first used for the television coverage.

The leading television commentator in France was a former rider, Robert Chapatte. At first he was the only commentator. He was joined in following seasons by an analyst for the mountain stages and by a commentator following the competitors by motorcycle.

Broadcasting in France was largely a state monopoly until 1982, when the socialist president François Mitterrand allowed private broadcasters and privatised the leading television channel. Competition between channels raised the broadcasting fees paid to the organisers from 1.5 per cent of the race budget in 1960 to more than a third by the end of the century. Broadcasting time also increased as channels competed to secure the rights. The two largest channels to stay in public ownership, Antenne 2 and FR3, combined to offer more coverage than its private rival, TF1. The two stations, renamed France 2 and France 3, still hold the domestic rights and provide pictures for broadcasters around the world.

The stations use a staff of 300 with four helicopters, two aircraft, two motorcycles, 35 other vehicles including trucks, and 20 podium cameras.

Hélicoptères de France (HdF)

Video Provided by:

French aviation company Hélicoptères de France (HdF) has provided aerial filming services for the Tour since 1999. HdF operates Eurocopter AS355 Écureuil 2 and AS350 Écureuil helicopters for this purpose, and the pilots undergo training along the course for six months before the race.

Domestic television covers the most important stages of the Tour, such as those in the mountains, from mid-morning until early evening. Coverage typically starts with a survey of the day’s route, interviews along the road, discussions of the difficulties and tactics ahead, and a 30-minute archive feature. The biggest stages are shown live from start to end, followed by interviews with riders and others and features such an edited version of the stage seen from beside a team manager following and advising riders from his car. Radio covers the race in updates throughout the day, particularly on the national news channel, France Info, and some stations provide continuous commentary on long wave. The 1979 Tour was the first to be broadcast in the United States.

In the United Kingdom, ITV obtained the rights to the Tour de France in 2002, replacing Channel 4 as the UK terrestrial broadcaster. Channel 4 coverage had been broadcast for the previous 15 years with episodes introduced with a theme written by Pete Shelley. The coverage is shown on ITV4, having aired in previous years on ITV2 and ITV3. Initially, live coverage was only broadcast at the weekend but since the 2010 Tour de France, ITV4 has broadcast daily live coverage of every stage except the final which is shown on ITV, ITV4 have the nightly highlights show.

Covering the Tour

On 1 February 2011, Canada’s TSN announced that they had acquired the rights to the Tour de France in a “multi-year” deal, which ultimately lasted for three years; the rights were acquired by Sportsnet in 2014.

The combination of unprecedented rigorous doping controls and almost no positive tests helped restore fans’ confidence in the 2009 Tour de France. This led directly to an increase in global popularity of the event. The most watched stage of 2009 was stage 20, from Montélimar to Mont Ventoux in Provence, with a global total audience of 44 million, making it the 12th most watched sporting event in the world in 2009.

Tour de France FAQs

-

How long is the Tour de France?

This year’s Tour is 3,328 kilometers (2,068 miles). As with every year, the race consists of 21 stages over the course of three weeks. There are three rest days where there is no racing this year. There are two time trials this year, one in Copenhagen on the opening day of racing and the second on the penultimate stage of the race.

-

How do you win the Tour de France?

The rider with the lowest overall time after 21 stages wins. There are also stage winners each day, where the first racer across the line wins.

-

What was the longest Tour de France stage?

The longest Tour de France stage on record was in 1920, where the fifth stage was 482km / 300mi long! These days, stages average around 175km / 109mi. The longest stage this year is stage 6 from Binche to Longwy, which stretches out for 220.2km in length. The shortest stage is stage 1 in Copenhagen, with the winner of the first yellow jersey destined to set the fastest time in the opening 13.2km time trial.

-

What is a peloton?

The largest group of riders on the road, the peloton is also called the “pack” or the “bunch.” By riding in a pack a rider uses 30 percent less energy than he would riding alone. A chasing peloton often has an advantage over a smaller breakaway.

-

What is an echelon?

When wind batters the peloton from the side the riders split into smaller angled lineups to capitalize on each other’s draft. Echelons take on a formation much like flying geese, however an echelon’s size is determined by the width of the road. So, in crosswinds, smart riders can use echelons to distance their rivals.

-

What is a domestique?

A rider who sacrifices his own ambitions in order to aid his team leader. A domestique rides into the wind to shield his team leader; he also carries extra water bottles and food for the leader. If the leader has a puncture, the domestique may give up his wheel or bicycle, or wait to pace the leader back into the peloton.

The Tour is an important cultural event for fans in Europe. Millions line the route, some having camped for a week to get the best view.

The Tour de France appealed from the start not just for the distance and its demands but because it played to a wish for national unity, a call to what Maurice Barrès called the France “of earth and deaths” or what Georges Vigarello called “the image of a France united by its earth.”

2023 Tour de France Stage Results

| Stage | Date | Course | Distance | Elevation gain[9] | Type | Winner |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 July | Bilbao (Spain) | 182 km (113 mi) | 3,242 m (10,636 ft) | Medium-mountain stage | Adam Yates (GBR) |

| 2 | 2 July | Vitoria-Gasteiz to San Sebastián (Spain) | 209 km (130 mi) | 2,943 m (9,656 ft) | Medium-mountain stage | Victor Lafay (FRA) |

| 3 | 3 July | Amorebieta-Etxano (Spain) to Bayonne | 193.5 km (120.2 mi) | 2,600 m (8,500 ft) | Flat stage | Jasper Philipsen (BEL) |

| 4 | 4 July | Dax to Nogaro | 182 km (113 mi) | 1,434 m (4,705 ft) | Flat stage | Jasper Philipsen (BEL) |

| 5 | 5 July | Pau to Laruns | 163 km (101 mi) | 3,922 m (12,867 ft) | Mountain stage | Jai Hindley (AUS) |

| 6 | 6 July | Tarbes to Cauterets (Cambasque) | 145 km (90 mi) | 3,219 m (10,561 ft) | Mountain stage | Tadej Pogačar (SLO) |

| 7 | 7 July | Mont-de-Marsan to Bordeaux | 170 km (110 mi) | 785 m (2,575 ft) | Flat stage | Jasper Philipsen (BEL) |

| 8 | 8 July | Libourne to Limoges | 201 km (125 mi) | 1,812 m (5,945 ft) | Hilly stage | Mads Pedersen (DEN) |

| 9 | 9 July | Saint-Léonard-de-Noblat to Puy de Dôme | 182.5 km (113.4 mi) | 3,949 m (12,956 ft) | Mountain stage | Michael Woods (CAN) |

| 10 July | Clermont-Ferrand | Rest day | ||||

| 10 | 11 July | Vulcania to Issoire | 167.5 km (104.1 mi) | 3,127 m (10,259 ft) | Medium-mountain stage | Pello Bilbao (ESP) |

| 11 | 12 July | Clermont-Ferrand to Moulins | 180 km (110 mi) | 1,854 m (6,083 ft) | Flat stage | Jasper Philipsen (BEL) |

| 12 | 13 July | Roanne to Belleville-en-Beaujolais | 169 km (105 mi) | 3,088 m (10,131 ft) | Medium-mountain stage | Ion Izagirre (ESP) |

| 13 | 14 July | Châtillon-sur-Chalaronne to Grand Colombier | 138 km (86 mi) | 2,413 m (7,917 ft) | Mountain stage | Michał Kwiatkowski (POL) |

| 14 | 15 July | Annemasse to Morzine | 152 km (94 mi) | 4,281 m (14,045 ft) | Mountain stage | Carlos Rodríguez (ESP) |

| 15 | 16 July | Les Gets to Saint-Gervais-les-Bains | 179 km (111 mi) | 4,527 m (14,852 ft) | Mountain stage | Wout Poels (NED) |

| 17 July | Saint-Gervais-les-Bains | Rest day | ||||

| 16 | 18 July | Passy to Combloux | 22.4 km (13.9 mi) | 638 m (2,093 ft) | Individual time trial | Jonas Vingegaard (DEN) |

| 17 | 19 July | Saint-Gervais-les-Bains to Courchevel | 166 km (103 mi) | 5,405 m (17,733 ft) | Mountain stage | Felix Gall (AUT) |

| 18 | 20 July | Moûtiers to Bourg-en-Bresse | 185 km (115 mi) | 1,211 m (3,973 ft) | Flat stage | Kasper Asgreen (DEN) |

| 19 | 21 July | Moirans-en-Montagne to Poligny | 173 km (107 mi) | 1,950 m (6,400 ft) | Medium-mountain stage | Matej Mohorič (SLO) |

| 20 | 22 July | Belfort to Le Markstein | 133.5 km (83.0 mi) | 3,484 m (11,430 ft) | Mountain stage | Tadej Pogačar (SLO) |

| 21 | 23 July | Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines to Paris (Champs-Élysées) | 115 km (71 mi) | 598 m (1,962 ft) | Flat stage | Jordi Meeus (BEL) |

Related Events

L’Étape du Tour

L’Étape du Tour (French for ‘stage of the Tour’) is an organised mass participation cyclosportive event that allows amateur cyclists to race over the same route as a Tour de France stage. First held in 1993, and now organised by the ASO, in conjunction with Vélo Magazine, it takes place each July, normally on a Tour rest day.

Tour de France Femmes

From 2022, Tour de France Femmes – an 8-day stage race in the UCI Women’s World Tour – was held following the Tour, replacing La Course.[235] The Tour de France Femmes had its first stage on the Champs-Élysées prior to the final stage of the men’s race.[10] The announcement of the race was praised by the professional peloton and campaigners.[236][237] The first edition was won by Dutch rider Annemiek van Vleuten, completing a Giro – Tour double in the same year.[90]

Unfortunate Deaths During the Tour de France

1910

French racer Adolphe Hélière drowned at the French Riviera during a rest day.

1935

Spanish racer Francisco Cepeda plunged down a ravine on the Col du Galibier.

1967

13 July, Stage 13: Tom Simpson died of heart failure during the ascent of Mont Ventoux. Amphetamines were found in Simpson’s jersey and blood.

1995

18 July, Stage 15: Fabio Casartelli crashed at 88 km/h (55 mph) while descending the Col de Portet d’Aspet.

Enter to win a trip to the 2024 Tour de France (not really 😉 )

Complete the form below for a chance to enter.

- Fast & Flat

- Mountainous

- Rolling Terrain

- Tadej POGAČAR

- Mathieu VAN DER POEL

- Thomas PIDCOCK

- Wout VAN AERT